Centre For Local Research into Public Space (CELOS)

Finding the Village in the City

back to Jutta's Blog main page

1.The Village

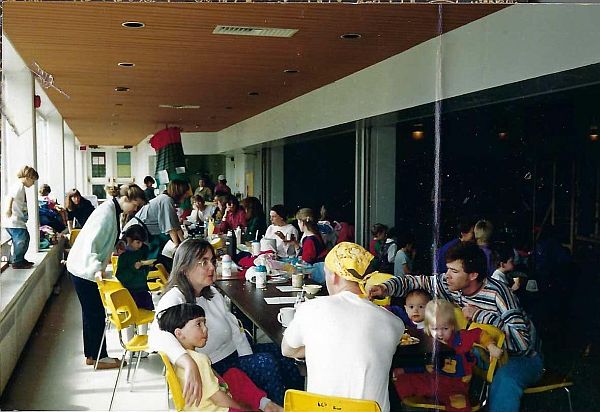

the long tables, the sun through the windows

In the big city of Toronto, in a Parks and Recreation Department community centre located a bit west of downtown, there was once a village that you could only find on Thursdays. If you went there on a sunny Thursday afternoon in the fall, you would get a clue of its presence even before you got inside the centre. Beside the usual outdoor playground structure of colourful plastic tubes and bridges, there would be a tipi, with a thick felt cover, made of gray and red and orange wool. There might be some kids inside the tipi. Up the hill, beside the chain-link fence that separates the park from the neighbouring alley-way, two women -- one with a baby in a sling on her back – might be digging in a flowerbed, and tearing dead morning glory vines off the fence, to clean up after the summer. They’d give you directions to the gym, to the "indoor park."

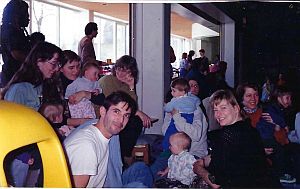

You would barely get the gym door open before you smelled the soup at the café counter, and the refried beans, and the fresh muffins, and the coffee. There would often be flute music playing on a little tape deck, and about forty or fifty people, mostly adults, mostly women, would be talking and eating at four long tables set up in an open area, adjacent to the gym. The tables often looked pretty chaotic: bag lunches, plates of café food, somebody's knitting, here and there a pile of books, a few jars of flowers, some baby washcloths for sticky faces, a sewing project, and many, many odd cups that look like they came from garage sales -- all these things would be scattered along the length of the tables. The sun would often be pouring in through the floor-to-ceiling south-facing windows -- one wall was all glass. The long window-ledge would be piled high with coats and bags.

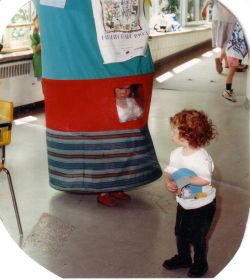

To see what was going on inside the gym, you’d have to skirt around a red-and-green cloth tube, about four feet in diameter and nine feet high, suspended from hooks on the ceiling, and reaching to within a foot of the floor. This tube always had notices pinned all over it: a bulletin tube. Near the bottom there was a little clear plastic "window" sewn into the fabric, and if you bent down to look at it, little faces would be looking out at you: kids who had ducked under there, pretending it's a clubhouse.

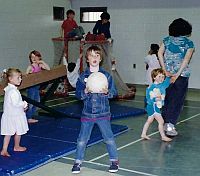

In the middle of the gym there was always a plastic climber, and some older kids – usually about a dozen of the children were of school age – might have pushed a wooden climber next to the plastic one and hooked the two structures together with a ladder. They often added a side room to their "castle," using some colourful plywood-and-fabric curved walls of varying heights. These walls had a slightly rickety, homemade look. A few more of the curved walls were laid on their sides so as to make a big tunnel. The fort was often being vigorously defended with hockey sticks doubling as medieval lances, as little invaders swarmed all around it, but despite some impressive posturing, nobody would be getting seriously clobbered.

On the west side of the gym two hockey nets were set up, and eight boys plus somebody's father were using the hockey sticks for their intended purpose. The pace of the play was spirited, but from time to time it would slow down, as some little two-year-old wandered in one side of the game and out the other. The boys skillfully played around these moving obstacles or, every once in a while, stopped the game, lift the little person off and deposited them back with the admiring audience of babies-to-toddlers sitting on the benches. If you were to say something about the danger of injury with such a strange age mix, somebody would probably tell you that in all the years of the indoor park, there had been only two very minor injuries. A far better record, they'd say, than many playgrounds with more rules and more supervision. And indeed, if you watched a bit longer, you might notice the elegance with which the older kids were avoiding the intruders. Like Wayne Gretzky, they played as though they had eyes in the back of their heads.

On the east side of the gym, little troubadors -- wearing odd costume combinations from the costume-basket – might be arranging chairs into a makeshift theatre. There would be some women sitting on mats talking to each other, nursing their babies and watching the preparations. At a table nearby, other women might be working on making some stuffed-sock hobby horses for the troubadors. If you were to stroll by, you might hear them talking about the politics of South Africa.

But perhaps by now you'd probably be getting hungry. You could go back to the café counter, where a little crowd of ESL students from the classrooms upstairs, mostly older women, often came for their snack and their coffee, joking in Spanish with Isabel, the cook. The food line-up was right beside the farmer's market table. Here a farmer would arrange kale, cabbages, pumpkins, herbs and goat's cheese from her farm, two hours out of town. Framed by the gay canopy over the market-table, she would sit beside her fine harvest display. There were also two other tables of used clothes for swapping, which would be getting earnest attention from the people waiting in line for food.

every community centre used to have a woodshop

And so you might sit and watch and eat your lunch, maybe even strike up a conversation. The talk at the tables ranged from the usual homey advice on kids and shopping, to hints about apartments to rent, arrangements for job-sharing, or opinions on movies, books, or the political questions of the day. All around you the sound of talk and shouts and banging hockey sticks would rise and fall. But at some point in the afternoon, all the voices would often blend together and suddenly form a kind of tidal wave of noise, and that might seem to give quite a few people the same idea around the same time. Over the next few minutes about two dozen people would clear out to go for a swim at the pool, and another fifteen or twenty would go upstairs to the wood shop (returning much later with wooden trains, or swords, or fantastical structures made of odd-shaped wood scraps). The little medieval knights and damsels would go outside to play tag, and football, on the hill. Even though there were still many people left in the gym, it would gradually get quieter and quieter, almost drowsy, with the flute music and the sun shining in. At the end of the afternoon there might be a few final bursts of games and conversation, and then, around five-thirty, the people would gradually disperse and the village would fade away for another week. Perhaps, as you were leaving along with the others, you'd pass by the old men playing cards in the upstairs sitting area. They would look unsurprised by the slow exodus of this village; by the children carrying their wood-shop swords and the parents carrying their cabbages. The old men had been watching this Thursday procession for years, and they would most likely just grin and keep on playing cards.

2.The Beginning

The old men might not be surprised, but it still surprises me sometimes, to think that the start had been so simple. In 1985 I approached the co-ordinator of the Wallace-Emerson community centre on behalf of six friends, asking if we might use the gym to provide an indoor play-place for our small children, once a week, during the cold Toronto winter. We specified we didn't want any set programs: we wanted a place that was like a park, open to anyone at any time. The co-ordinator raised his eyebrows about the no-program idea but said, go ahead. On the first Thursday there were 27 people (counting the kids). Friends told friends, and on the second Thursday there were twice that many. For a few months attendance fluctuated, and then steadily began to grow. Any anxieties we'd had, about proving we could bring in enough bodies, went away.

The beginning was a bit shaky, as beginnings often are. On the second Thursday we left the teacups to drip dry in the dishrack, and when we came back on the third Thursday, we got a talking-to about putting dishes away and leaving the gym exactly as we'd found it. That was discouraging, because to us it seemed like such a miracle that we had even managed to bring lunches and toys and music, and had set up equipment and dragged out mats with our toddlers hanging onto our knees, and then managed to dismantle everything again. We found we had to do everything ourselves because this was a community project, not part of the recreation schedule. That was how it was seen at that time.

a spot for a community garden?

As more people came, those of us who had started the indoor-park often left the centre quite exhausted. Eventually it grew to be too much for us to do. The people who worked there agreed to take on the indoor-park as part of their official program. From then on they set up the heavy equipment for us and dismantled it afterwards. That made everything easier. One of the staff people opened the woodshop to us, and swimming hours were added. Even more people came, and over the years, others left, of course, sometimes to return again when another baby was born. There was sometimes live music, and theatre, and certain things happened that one might expect to see in a village. One year two people -- a single mother and a young man who used to accompany a disabled friend -- fell in love and moved in together; and another year one woman bought another woman's house; another time we went to a meeting at city hall and asked for money for a "paid mother" -- sort of like a village warden -- to help out at the indoor park, and they said yes; twice we tried to start some vegetable gardens at the far end of the park by the chain-link fence, but failed to get permission; and during that whole time many babies learned to walk and then to talk, and many clothing swaps were made, and innumerable stories were told. In this way many people found friends there.

older kids as well as younger ones

The place in a sense became a kind of one-day-a-week community. Communities where people really see each other often (as opposed to "communities" like most city neighbourhoods, where many of the people hardly even recognize each other) develop different characters according to the people who are there. And as people move away and new people come, that character changes. But it doesn't change totally, since communities where people know one another also hold on to their stories -- their history. It happened that this indoor-park was started by women who breast-fed their babies. So did the friends they brought in. Many looked after their children longer than is now the norm (instead of quickly returning to their jobs), which meant they didn't have a lot of money. There were also some babysitters, and grandparents, and men and women who had paying jobs on the other days. But somehow the culture of breast-feeding and mother-reared children predominated, perhaps partly because women who look after their children longer seem to be the main people who have a bit of time left to be neighbourly. The indoor park also generally included a number of single mothers scraping by on some kind of welfare. And from the third year on it always seemed to have a dozen or so home-schooled children as well. As in an old-time village schoolhouse, these older children often helped out the younger ones, and the younger ones learned new games from imitating the older ones.

3.The Showdown

This village was not the only "culture" at the centre. One of the interesting and difficult things about urban community centres is that they often have eight or nine separate cultural groupings which all exist in the same building. That was true of this centre. Among these groups the indoor park was always unusual. It wasn't built around a program. It had few planned activities. It seemed more like a pause, a kind of lingering over play and conversation, a lull. The sun shone in through the windows as the music played on the tape deck. To the people who came on Thursdays, it was an oasis from the ordinary hustle of the days. But what felt like an oasis from the inside was a strange, unregulated thing from the outside, and as more people came, the indoor park began to be a problem for the centre.

This is not surprising. It seems to me that, in a certain way, the closer that a collection of people comes to being a community, the harder they make the job of the people who work at a community centre. This is evident whenever a close-knit ethnic group begins to use a community centre, or a group such as our "indoor-park." Such a group is not a class, not a program, not even an age group that can be organized, or confined to one room. There are children, and grandparents, and people who just want to talk to one another, and people who have odd ideas and who want to argue. They may spread out all over the centre, going into the kitchen to make tea and the office to use the telephone. They develop a sense of ownership. They tend to sink roots into a place and get stuck there. Sometimes they can't be budged, and then, just by their presence, they can make a mess of everybody else's schedule. This is not their intention. It's a consequence of their being a community, with all its variety and intensity. But even though they intend no harm, they cause trouble.

nobody wanted to leave

In the fourth year of the indoor park there was a showdown between the staff and the people who came on Thursdays. A gymnastics class was scheduled on Thursdays right after school. The caretakers wanted the gym to be emptied by about three, so that they could clean it and let it sit for a bit before the pupils arrived at four. But the conversation at the indoor park was often so engaging, the games so much fun, that the people at the indoor park just stayed where they were, oblivious of the time. Warnings were given but they always worked only for a week or two, and then there was back-sliding. When the gymnastics class started, there would still be people hanging around, and sometimes the little children would imitate the actions of the gymnasts, or would go on playing their own games at the sidelines.

One Thursday at three o'clock sharp, three serious-looking staff people came into the gym. One of them had a key for lowering the metal barriers between the eating area and the gym. She asked those sitting in the way to move and -- CLANG!! CLANG!! -- down came the barriers. The startled children came running out of the gym, and the adults hurriedly gulped their tea, put on their coats, gathered up their bags and their babies and left by the nearest doors. In this way the community was evacuated from the community centre.

By that time I had become the acknowledged "mother" of this indoor park, the one who had been there continuously since the start, the one who took care, along with the "paid mother," of the many odds and ends that need tending when so many people come together. I had heard a good deal of talk, over the years, about the intention of the Recreation Department to "develop community." I wrote a letter to the staff of the centre and sent a copy to the head of the Recreation Department. Did they know what they had on Thursday? I asked. Surely we were part of the very community they were looking for? Could people not be allowed to stay and watch the gymnastics from the sidelines? Did there have to be such a clear line between one activity and the next? Did "community" have to be programmed? And if the "community" had to leave the centre after a set number of hours, where else could community life play itself out? Was there any remaining public space that wasn't a school, or a church, or a mall?

I was fairly certain the response to my letter would be more of the same CLANG. Clearly the tempo of the indoor park didn't fit with the community centre's schedule. And as long as we had to clear the place at 3.00 sharp, I felt there would always be a need to harrass people into leaving. Doing this was so unpleasant to me that I counselled the others just to let the indoor-park die. I told the staff that we’d taken the hint, and wouldn’t be coming back.

Here I have to admit something: I was secretly glad to be able to stop the hard work of all those Thursdays, of introducing lonely newcomers into a hundred different conversations, and picking up mountains of muffin crumbs and lost socks, and thinking up play structures that could be built for no money, and all the other things. The "village in the city" would have the righteous indignation of being forced out, and at the same time I'd have the relief of getting this indoor park, which had turned out so much bigger than I had expected, off my back.

But that's not what actually happened, not at all. Instead, there was a flurry of meetings and phone calls and visits from other people in the Recreation Department. Instead of a door shut in our faces, we got a kind of recognition, a sense of being invited guests at the party, not intruders. We were told by the management, and shown, that we were welcome, that they had seen our point, that they were willing to make accommodations, and that there would be no more CLANG. Even as I realized rather wearily that my hectic Thursdays were not over after all, I was very moved.

4.Separate Realities

This odd little village continued to exist for more than another twenty years, sometimes very beautifully. New people kept peering around the door and old ones went off, full of stories, on to the next stage of their lives. But this is not a fairy tale, and we haven't lived happily ever after. The problem of conflicting uses of the community centre didn't just melt away, nor did the problem of conflicting cultures. The presence of this village continued to be hard on the people who worked at the centre. They endured the unpredictable, chaotic Thursdays, and waited for the relative normalcy of the rest of the days. The task of getting to know one's neighbours is very slow: the benefits accumulate only gradually, over years. The quick energy of the recreation worker's athletic spirit seemed ill placed here, and they weren't much inclined to talk over a cup of tea. Besides that, the people who came to the indoor park sometimes seemed ungrateful and grabby. They complained, over and over again, when the street doors were locked and they had to find other ones that were open, or when the woodshop was cancelled, or when they couldn't find a broom to sweep up, or when the dishes were locked away and no one could find the key. They made the floor and the exercise mats sticky, and left juice spills in the corner. Occasionally some of them were outrageous and peremptory, acting as though they owned the place, giving people orders. This was very hard for the staff.

Such people troubled me too, of course, and I didn’t even get paid for being ordered around like that. But still, the whole sticky, populous group looked different to my eyes. I have wondered why that is, and have come up with this reason: Even though some of these people lived a distance away, they were all in a sense my neighbours, whose fate I shared at that time as a mother of children and a person anxious about the fragility of whatever community life remains in the city. I can't choose other neighbours, nor get away from the ones who seem eccentric or troubled. I have to stick it out, not because I am a community centre worker who is employed to service the community even-handedly, but because later on fate will wash up neighbours at my children's doors as it washes them up at mine, and it seems essential that we help one another now, and practice loyalty and even love with one another, so that the world of our children might be a tolerable place for them to live in. For me, an indoor-park-which-is-a-kind-of-village-inside-a-community-centre was one place where people could practice friendship. For a time.

This slightly evangelical sense of mission on behalf of my children and my neighbours was a comfort to me, a way to justify having to do things I'd rather not do on certain difficult Thursdays. The staff of the centre didn't seem to have that comfort. As part of their jobs, they had to unlock and lock the doors, answer the phones, register the classes, and so on; they had to manage, and draw up schedules, and write reports, and show a census, and worry about cutbacks. They couldn't warm themselves on the friendships with neighbours that take so much time to develop.

One day, a man who worked at the centre said to me, in a moment of discouragement: having a job at a place like this is like having children. You have to give and give and you almost never get thanks. I wanted to say: but no, that's not what having children is like at all, not at all! But I couldn't say it: his telephone rang just then. Later he said: everyone cares only about what they're going to get. People complain, but they never thank us.

Perhaps he's right. In the case of the particular "village" I've described, how much connection could there be between the people who came there, precariously practising friendship, and recreation managers who are supposed to develop community, and gender equality, and drug awareness, and an active lifestyle, in hundreds of people, and new ones all the time? At times the centre seemed much closer to a processing-plant than a human-scale community. In such a situation, the moments for people to express their gratitude to one another might be very rare.

And yet the gratitude was there. Against many odds, a whole garden of friendships grew up in a community centre, because the people who worked there allowed it to grow naturally, on its own, despite the headaches that this rather unruly garden gave them. It's unclear to me whether the recreation workers understood how important their gift of tolerance was in the lives of the many people who have passed through this "village." But I think I understand it, and I'm thankful.

Many people passed through this "village."

Show search options

Show search options

You are on the [Village In City Update] page of folder [Research Library ]

You are on the [Village In City Update] page of folder [Research Library ] For the cover page of this folder go to the

For the cover page of this folder go to the